The Millennial Juror:

Friend or Foe to the

“Big Corporate” Litigant?

A few years ago, in an asbestos jury selection in Wilmington, Delaware, jurors came into a conference room one by one to be questioned, as is the procedure in that venue. At the head of the table sat the magistrate in his black robe. To his right sat four attorneys for the plaintiff and, on the other side, twice as many attorneys representing the remaining defendants in the case. Among the many questions posed to each prospective juror was one that has been heard in jury selections for many years all over the country, “What are your feelings about big corporations?” Most replies were neutral, but one man said, “Big corporations are the backbone of the economy.” Plaintiff’s counsel moved to strike the juror for cause, but the magistrate denied the motion and they ended up exercising a peremptory.

The plaintiff’s strike and the disappointment on the defense side were both in line with academic research. Valerie Hans, a professor of social sciences in the Cornell School of Law and recognized authority on jury decision making, even wrote a book about it: Business on Trial, The Civil Jury and Corporate Responsibility (Hans, 2000). Jurors’ feelings about “big corporations” fall on the Michael Moore – Dick Cheney continuum. Michael Moore jurors tend to believe big corporations are the root of all of society’s ills, while Dick Cheney jurors would agree with that pro-business Wilmington juror. In an injury or products case where a private individual is suing a corporation, the plaintiff would like a jury of 12 Mikes, while the defendant hopes for as many Cheneys as the litigation gods will allow. The correlation between opinions about corporations and civil verdict propensities has been well established in the academic literature and has contributed to conventional wisdom in jury selections for decades. But a recent study conducted by the trial consulting firm, DecisionQuest, suggests conventional wisdom might need some reconsideration with the potential cause for reassessment of this truism – the existence of the Millennial juror serving on today’s panels.

Why do we set forth this hypothesis about our fine Millennials? A bit of setup is in order. Beginning in March 2020, DecisionQuest conducted a series of studies on how the COVID-19 pandemic might be impacting juror decision making. This study followed in the tradition of ones DecisionQuest had conducted after other social and economic crises like the Enron scandal, 9/11 and the Great Recession. The coronavirus pandemic survey project consisted of three “waves” of online surveys with about 900 respondents in each wave (for details see Bettler, 2021 [1]). The aggregated data from the three waves comprises 2,785 respondents from eight major cities.

The survey began with a series of questions about the respondents’ life experiences (e.g., Have you ever worked in the medical field? Have you ever served on a jury?) and, among other things, their opinions about corporations. After these preliminaries, they responded to three case summaries. In this manner, each respondent reported his or her verdict “leaning” in three case types, like an asbestos case, a sexual harassment case, or others [2]. From these verdict ratings, each was given a generalized pro-plaintiff or pro-defendant score. Overall, 51% of the sample fell on the plaintiff side of the line and 49% on the defense side. This 51% represents a rough baseline probability against which we can check for factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of a plaintiff verdict. Although this is a crude measure of verdict propensities, anyone who has ever picked a jury knows, there definitely is such a thing as a generalized pro-plaintiff or pro-defendant predisposition.

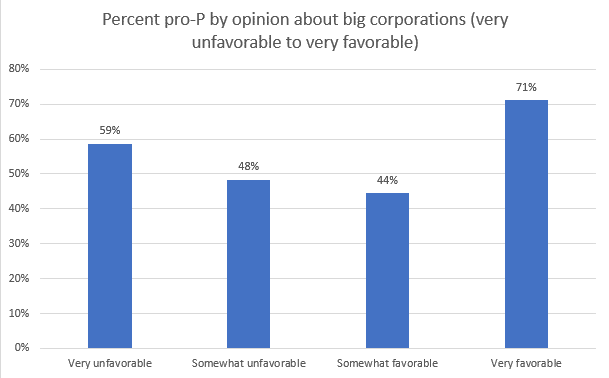

Since each respondent also answered the question, “What is your general opinion of most large corporations? (very unfavorable, somewhat unfavorable, somewhat favorable, or very favorable),” it is possible to correlate this with each respondent’s verdict propensity, yielding the following:

The results of this analysis are at odds with 20+ years of jury decision-making research. The people who were “very unfavorable” toward large corporations (far left bar), as expected, found for the plaintiff 59% of the time, significantly above the base rate. “Somewhat unfavorable” and “somewhat favorable” respondents were decreasingly pro-plaintiff (or increasingly pro-defense), which is also in line with past experience. But people who were “very favorable” towards corporations went markedly against expectations and actually found for the hypothetical plaintiffs at the highest rate, 71%.

What might account for this counter-intuitive finding? A meta-analysis of hundreds of past jury research projects is underway by the trial and jury consultants at DecisionQuest, but, in the interim, a few suggestive observations can be offered.

Overall, opinions toward corporations were positive. Of the total 2,785 respondents, 61% were “somewhat favorable” or “very favorable” toward large corporations and 39% were unfavorable. But when the sample was split by generations [3], the older respondents were the least favorable toward corporations and Millennials were the most positive. Among Baby Boomers, only 5% were “very favorable,” while more than four times that rate, 22%, of Millennials reported “very favorable” opinions about “most large corporations.” As is usually the case, most people were in the middle with “somewhat favorable” views.

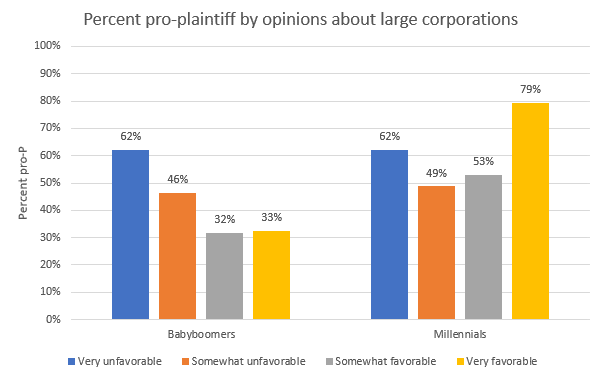

As mentioned above, the sample, in general, was 51% pro-plaintiff, but when we look at the generations and their opinions about corporations separately, the following pattern emerges:

In line with past research and the conventional wisdom of attorneys like the ones in that Delaware courthouse conference room, the more pro-business Baby Boomers were, the more likely they were to find for the defense. Baby Boomers who strongly disliked corporations found for the plaintiff 62% of the time, but those who were favorable to big business found for the defendant almost 70% of the time. Millennials who were “very unfavorable” toward big corporations (blue bar in the right cluster) found for the plaintiff at exactly the same elevated rate as the Baby Boomers, 62%, but in the younger cohort, even though they were generally more pro-business, the relationship is partially reversed: the most pro-business Millennials were also the most pro-plaintiff!

What might account for this generational reversal? A meta-analysis of past DecisionQuest research, aggregating 20+ years of data from hundreds of surveys, mock trials and focus groups and tens of thousands of jury-eligible research subjects, is in progress to address this question, but, in the meantime, it seems Millennials are generally more pro-plaintiff than Baby Boomers: 59% vs. 38% – significantly above and below the baseline, respectively. Perhaps it is not entirely coincidental that the “blockbuster” verdicts of recent years began precisely when Millennials started predominating in American jury boxes [4]. Perhaps because Millennials have the highest expectations about corporate behavior, they are the most inclined to punish companies that violate those expectations.

Be that as it may, the correlations and conventional wisdom that guided jury selections 20 years ago may no longer be predictive. Plaintiff attorneys, like the ones who struck the Wilmington juror for his pro-business views, might be knocking millions of dollars off their ultimate verdicts with an ill-informed peremptory strike if this counter-intuitive trend holds true. And, corporate attorneys who expect pro-business jurors to put the freeze on an outrageous damages award might find the final verdict much warmer than they expected. The multi-billion-dollar verdicts of recent years might mean that Millennial jurors have metaphorically broken off from the ice shelf. Whether, or how much, this raises the sea level for big damages awards will be the subject of a future report.

About the Author:

Get to know Robert F. Bettler, Jr., Ph.D.

[1] View COVID-19 & Juror Attitudes: Insight from Our 2020 Longitudinal Research Study webinar and presentation slides here.

[2] Also contract, whistleblower, insurance, medical malpractice, and talcum powder cases.

[3] Per the Pew definitions, Baby Boomers were born between 1946 and 1964, Gen Xers-1965 to 1980, Millennials-1981 to 1996, and Gen Zers-born 1997 or later.

[4] See Bettler 2018 here.

Editoral Policy

Content published on the U.S. Legal Support blog is reviewed by professionals in the legal and litigation support services field to help ensure accurate information. The information provided in this blog is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice for attorneys or clients.